Editor’s note: Max Wolff is an economist and investment strategist who is the managing partner and chief economist at Manhattan Venture Partners. Previously, he has served as the chief economist at a leading financial technology and investment firm.

Editor’s note: Max Wolff is an economist and investment strategist who is the managing partner and chief economist at Manhattan Venture Partners. Previously, he has served as the chief economist at a leading financial technology and investment firm.

Many high-flying companies are pushing logistics, services, and

payment options to our new “sharing economy.” We see these firms and

sectors as largely driven by macroeconomic trends.

The American middle class is in steep decline, which has been true

for 3-4 decades but accelerated rapidly after 2008. Converging U.S. and

global macroeconomic change has created a millennial generation in

fierce competition for opportunity and armed with the Internet in the

search to reduce costs, find income and get ahead. Inter-generationally,

there are more mice, the mice are more hungry, and there is less cheese

in life’s maze.

Competition has increased as global barriers and technology change

have added mice into the maze more rapidly than new cheese has been

introduced.

Enter the “sharing economy.”

The sharing part of the sharing economy involves using the mobile

Internet to offer your property or labor to people who want to

substitute your efforts or you’re owned, rented or borrowed house,

apartment, car, bike for a traditional rental offering. This is likely

to subsidize or smooth the day, job, trip and ride of the buyer and

offers to add a few dollars to the coffers of the sharer. Likely, the

pool of folks trying to sell labor and rent their stuff will quickly

exceed the demand for services. There tend to be more servants than

masters in an economy with rising income inequality.

Coordinating piece work online or with mobile apps streamlines what

economists have studied and called “putting out systems” for 200 years.

These systems are widely credited with helping Western Europe transition

to capitalism from feudalism.

The sharing economy is part reality and part feel-good gloss and nod

in the direction of possible future outcomes. Folks love and use Uber,

Lyft, Via, Gett, Kuaidi Dache, Didi Dache, Ola, Easy Taxi…. because many

folks need and want to make more money and other folks are looking to

save on the costs of getting around, or have someone else do the work,

pay the cost and take the risk.

It is not clear that drivers are major beneficiaries in many cases.

The deregulatory adventurism that defines the space is undermining

traditional limits on the number of drivers offering services. Take

rates in the 25 percent range mean that 25 percent of total revenue

vanishes off the top and drivers are left to pay for gas, insurance,

cars, taxes, tickets with 75 percent of gross revenues. Recent work by

SherpaShare strongly suggests that, while initial incomes can increase,

long-term earnings are often at or below traditional compensation

structures with greater risk assumed.

There are few employees and thus, few traditional employee

protections. Instead all compete against all to be small individual

sellers of labor or renters of leased and financed property. Sounds like

the 19th century? It does if you know some economic history.

Long term, investor excitement around these companies suggests that

sharing economy models will increase profits while shifting consumption

patterns to allow the newly less affluent to purchase fewer goods but,

to buy, less expensive services. There is real value created. Selling

services into the sharing economy will be under constant price pressure

while consumers will save. We will see an economic evolution further

toward buyers of labor and further away from sellers of labor.

Airbnb works as well as it does because professionals, particularly

in global cities with crushing rents, need and want to afford to live

near where they work in exciting culture and innovation centers. Thus,

the supply and demand of apartments, rides and delivery services is the

simple expression of less time, less money and frenetic mobile lives and

schedules.

These companies are the incorporated clearinghouses of changing

global macroeconomic realities. Our interest in and understanding of

these businesses comes into focus using a macroeconomic lens. Lodging,

transportation and food are leading costs faced by most. Unbundling

purchases and turning many underemployed or underpaid people into part

time contractors/providers of goods and services makes sense as a coping

mechanism for those stressed by shifting macro realities.

Floods of new folks selling into these markets will pressure prices

downward. Platform, data and access control from a few large

corporations will allow high take rates to survive. This will contribute

to yawning income and wealth differentials. The transformation of

employees into independent contractors removes traditional benefit

provision and worker protections from the mix. As new strains arise so

too will new challenges to various sharing economy compensation

relationships.

Around the world there is an emerging middle and upper middle class

that is native mobile. Global millennials are already drivers of many

technologies and extensive disruption. As large as this group looms in

U.S. discussions, the world is much younger and more millennial than the

US. Globally, there are over 2.3 billion people under 20 years of age.

The younger emerging global middle has rising resources and wants

services from the vast population with less means. Driver services,

delivery services, food preparation and hospitality being dispatched and

coordinated by apps is simply the rising middle class of the developing

world in the process of going mobile. The precarious new middle is

accustomed to servants and service provision and also to being servants

and service providers.

The sharing economy may further accelerate the rise of emerging middle classes and decline of developed economy middle classes.

Markets are huge, global and fast evolving as the falling middle

class of the developed world separates into consumers and producers that

need to work harder, longer, more hours to make fraying ends meet. This

vast tide is combining with rising developing country middle classes.

Global macro is the lens through which we see these opportunities. Macro

trends are fueling the sharing economy and are also contributing to the

rise of developing middle classes and the declines in some developed

middle classes.

Globalization of Service Arrangement

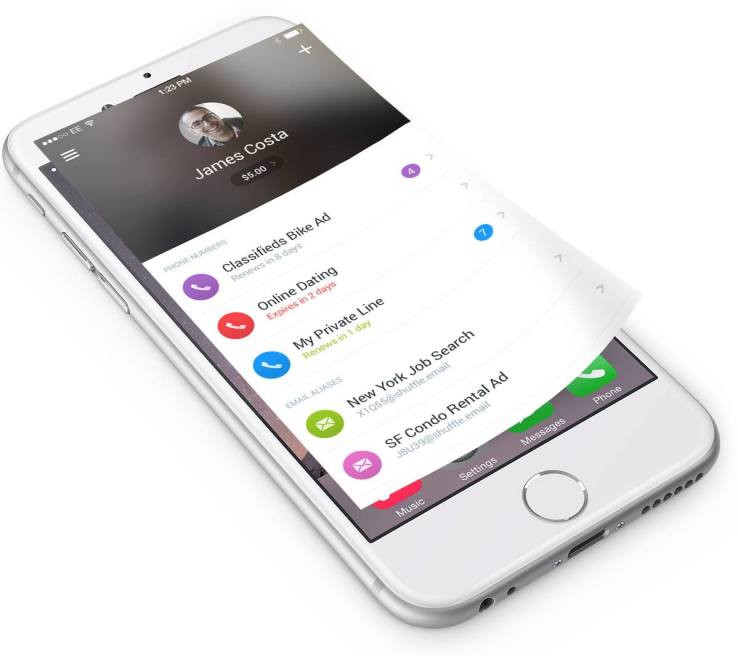

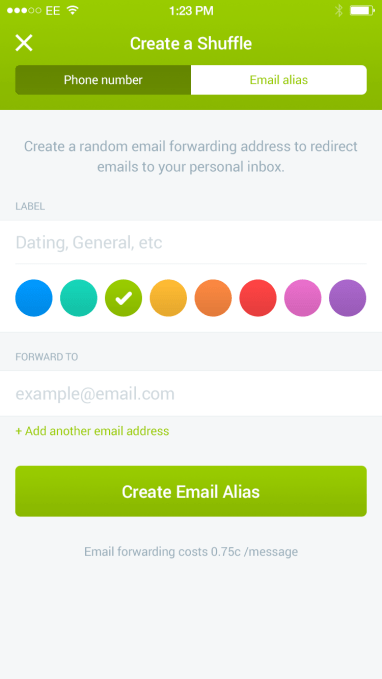

Needs and people can be matched on mobile apps as never before. Two

billion global webizens, and counting, are online. Online increasingly

means mobile devices such as smartphones and smart features on

traditional phones.

Google and Apple offer the world through their respective app stores.

Billions will soon have access to these stores and a billion already

do. Freemium business models and ad-supported services have lowered

costs and allowed bottom billions to consume free information, games, do

some basic financial transactions and offer their labor and property as

services.

The rapid globalization and size of the addressable market are

functions of macro trends in the price of basic smartphones,

urbanization and the rise of cash wages and markets. The vast majority

of people in the urbanized developing world need to sell labor services

where the crowds with money are accumulating.

The increasingly frail and precarious developed world middle class

needs to capture any and all revenue it can to stave off poverty. The

crowds are on the mobile web and app based extra money opportunities

sing an irresistible siren song. Mobile e-commerce is driving labor

services online. The small number of platforms and apps directing demand

traffic will have huge leverage and take home serious revenue from the

hordes trying to supplement or earn a living selling into perennially

well-supplied markets.

Editor’s note: Max Wolff is an economist and investment strategist who is the managing partner and chief economist at

Editor’s note: Max Wolff is an economist and investment strategist who is the managing partner and chief economist at

Editor’s note: David Klein is the CEO and co-founder of

Editor’s note: David Klein is the CEO and co-founder of

Design startup

Design startup  A new mobile app called

A new mobile app called

For the last seven weeks, the non-profit accelerator ‘

For the last seven weeks, the non-profit accelerator ‘ Editor’s note:

Editor’s note: