Europe’s Search Delisting Ruling Is Mostly About Social Media Privacy Invasions

It’s one year since the European Court of Justice made Wikipedia’s Jimmy Wales spit out his breakfast crumpet and spew crumbs of outrage all over the Internet.

It’s one year since the European Court of Justice made Wikipedia’s Jimmy Wales spit out his breakfast crumpet and spew crumbs of outrage all over the Internet.I am of course talking about the so-called ‘Right to be forgotten ruling‘ (rtbf) which extends European citizens’ personal data protection rights over search engine results by judging the latter data controllers, given the hierarchies of information their proprietary, closed-box algorithms generate.

For the past year, private citizens in European have the right to request that inaccurate, outdated or erroneous information that is served in a search result for their own name be delisted from said search. NB: No source material is removed from the Internet; the ruling purely relates to search results returned for private individuals’ names (public figures aren’t afforded the same rights if there is a public interest in knowing whatever information they want delisted — so there are some complex value judgements required to weigh up individual requests).

Google has fought tool and nail against the ruling — which is entirely unsurprising, given it threatens its commercial mission of organizing the world’s information and serving ads against it. Despite its opposed, Google set up an online process to accept and process requests last year — but given it’s a legal requirement it didn’t have a great deal of choice.

That said, Google is still resisting expanding search delisting to the Google.com domain, as European data protection regulators would like it to — currently only applying delisting decisions to European sub-domains. So get your popcorn for a future fight there.

RTBF data

Reputation VIP, an online reputation management company which in June last year set up a helper service for Europeans wanting to file requests with search engines, has just released some new data to coincide with the anniversary of the ruling — noting that it has sent just over 61,500 URLs to Google since it opened the Forget.me site on June 24.

In the first three months of the service being live it notes that Google received an average of 1,500 requests per day. In the last three months the rate of requests was averaging 500 per day — which it notes represents around 180,000 requests per year. So you certainly can’t say there’s no appetite for the rtbf.

Google has also stepped up the rate at which it processes requests over the past year, with Reputation VIP charting a reduction in time taken per request — from 56 days last June to 16 days back in March, although this rate has fluctuated (but it’s not an exact science — Google’s Eric Schmidt himself bemoaned the fact that it was not the sort of process that will ever likely be automated).

Mountain View did release some details about how it processes rtbf requests last August. However it has been less forthcoming about releasing substantial data about the content of requests — so the types of information that typically gets delisted. Thus far it’s offered a few sample examples/anecdotes, making it hard to quantify and evaluate the value judgements and public interest decisions Google is making.

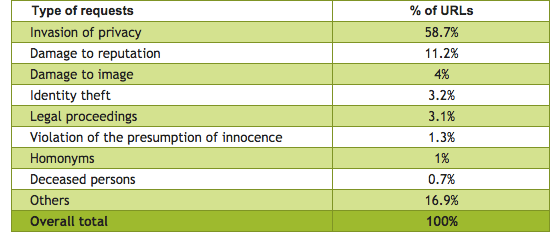

While Google has been reluctant to detail aggregated categories of requests, Reputation VIP has analyzed requests filed via its service to shed some light on the types of information European want delisted. It notes the predominant category by far remains ‘invasion of privacy’ — such as the disclosure of private addresses and religious or political affiliations against a person’s will. The next largest motivator for making a request is reputation damage:

Much of the criticism of the rtbf has centered on fears of criminals erasing bad behavior — leading to cries of censorship. But this data suggests those fears mischaracterize the mainstay of rtbf requests, with legal proceedings only accounting for a marginal 3.1 per cent of URLs, according to Reputation VIP.

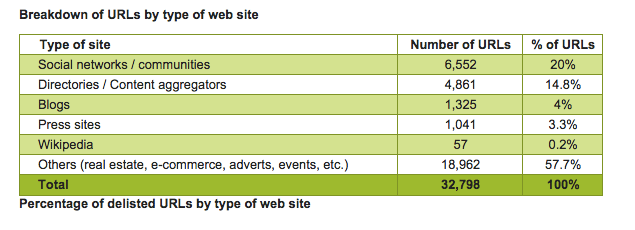

The media has also often been hugely critical of the ruling, arguing it threatens press freedom and freedom of expression — yet again this data suggests those fears mischaracterize what the rtbf is mostly being used for. It’s being used by private individuals, whose quotidian concerns wouldn’t make it into the press anyway, even if they have been posted to social media sites like Facebook.

Wikimedia — the organization which runs the Wikipedia online encyclopedia — has also been massively critical of the rtbf, dubbing it a ‘threat to its mission‘ last year. However according to this data just 0.2 per cent of URLs — or some 57 URLs — have pertained to information on Wikipedia over the past year:

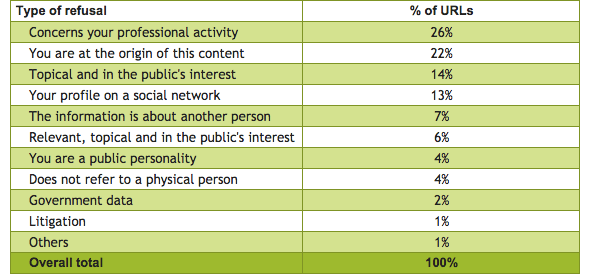

In terms of reasons for Google refusing a rtbf request, Reputation VIP’s data flags up that the primary reasons for delisting refusals are that the data concerns a person’s professional activity — which presumably weighs in on the public right to know balance requirement of the ruling — followed by the requester themselves being the originator of the data:

No comments:

Post a Comment